Articles

- Page Path

- HOME > J Korean Acad Community Health Nurs > Volume 33(3); 2022 > Article

- Original Article The Retention Factors among Nurses in Rural and Remote Areas: Lessons from the Community Health Practitioners in South Korea

- Hye Jin Park, Kyung Ja June

-

DOI: https://doi.org/10.12799/jkachn.2022.33.3.269

Published online: September 30, 2022

2Professor Emeritus, Department of Nursing, Soonchunhyang University, Cheonan, Korea

- 707 Views

- 48 Download

- 0 Crossref

- 0 Scopus

Abstract

Purpose

This study analyzed the retention factors of Korean community health practitioners who sustained over 20 years based on a multi-dimensional framework. This study suggests global implications for nurses working in rural or remote areas, even during a worldwide pandemic.

Methods: The participants were 16 Korean community health practitioners who worked in rural or remote locations for over 20 years. This study identified nurses' key retention factors contributing to long service in rural and remote areas. This is a qualitative study based on the narrative method and analysis was conducted using grounded theory. A semi-structured questionnaire was conducted based on the following: the life flow of the participants' first experience, episodes during the work experience, and reflections on the past 20 years.

Results: First, personal 'financial needs' and 'callings' were motivation-related causal conditions. The adaptation of environment-work-community was the contextual condition leading to intervening conditions, building coping strategies by encountering a lifetime crisis. The consequences of 'transition' and 'maturation' naturally occurred with chronological changes. The unique factors were related to the 'external changes' in the Korean primary health system, which improved the participants' social status and welfare.

Conclusion: Considering multi-dimensional retention factors was critical, including chronological (i.e., historical changes) and external factors (i.e., healthcare systems), to be supportive synchronously for rural nurses. Without this, the individuals working in the rural areas could be victimized by insecurity and self-commitment. Furthermore, considering the global pandemic, the retention of nurses is crucial to prevent the severity of isolation in rural and remote areas.

| J Korean Acad Community Health Nurs. 2022 Sep;33(3):269-278. English. Published online Sep 30, 2022. https://doi.org/10.12799/jkachn.2022.33.3.269 | |

| © 2022 Korean Academy of Community Health Nursing | |

Hyejin Park ,1

and Kyung Ja June ,1

and Kyung Ja June 2 2

| |

|

1RN, MPH, Department of Applied Health Science, Indiana University School of Public Health, Bloomington, Indiana, USA. | |

|

2Professor Emeritus, Department of Nursing, Soonchunhyang University, Cheonan, Korea. | |

Corresponding author: June, Kyung Ja. Department of Nursing, Soonchunhyang University, 31 Suncheonhyang 6-gil, Dongnam-gu, Cheonan 31151, Korea. Tel: +82-41-570-2492, Fax: +82-41-575-9347, | |

| Received March 26, 2022; Revised June 25, 2022; Accepted July 18, 2022. | |

|

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by- | |

|

Abstract

| |

|

Purpose

This study analyzed the retention factors of Korean community health practitioners who sustained over 20 years based on a multi-dimensional framework. This study suggests global implications for nurses working in rural or remote areas, even during a worldwide pandemic.

Methods

The participants were 16 Korean community health practitioners who worked in rural or remote locations for over 20 years. This study identified nurses' key retention factors contributing to long service in rural and remote areas. This is a qualitative study based on the narrative method and analysis was conducted using grounded theory. A semi-structured questionnaire was conducted based on the following: the life flow of the participants' first experience, episodes during the work experience, and reflections on the past 20 years.

Results

First, personal 'financial needs' and 'callings' were motivation-related causal conditions. The adaptation of environment-work-community was the contextual condition leading to intervening conditions, building coping strategies by encountering a lifetime crisis. The consequences of 'transition' and 'maturation' naturally occurred with chronological changes. The unique factors were related to the 'external changes' in the Korean primary health system, which improved the participants' social status and welfare.

Conclusion

Considering multi-dimensional retention factors was critical, including chronological (i.e., historical changes) and external factors (i.e., healthcare systems), to be supportive synchronously for rural nurses. Without this, the individuals working in the rural areas could be victimized by insecurity and self-commitment. Furthermore, considering the global pandemic, the retention of nurses is crucial to prevent the severity of isolation in rural and remote areas. |

|

Keywords:

Rural nursing; Community health nursing; Qualitative research; Grounded theory

|

|

|

INTRODUCTION

|

Health disparities between urban and rural areas, especially the shortage of health care providers in the rural community, are a non-resolved issue. To resolve the lack of primary health care providers, including rural and remote nurses, motivating and retaining primary health care providers in rural areas is an important issue [1, 2]. The historical background of the Community Health Practitioner (CHP) program in South Korea was based on the need for "Health for All", which arose as a goal of the World Health Organization (WHO); moreover, the Alma-Ata Declaration of 1978 emerged the significance of public health and primary health care [3]. This movement also influenced the Korean government to manage health problems in remote areas with less access to primary health care [4, 5]. The enactment of the 'Special Act for Healthcare in Rural Areas Act' described the role and activity of CHP as a primary healthcare provider and the public health center post; as a result, the first CHPs were assigned to the community posts [5].

Little is known about the retention factors compared to the literature on CHP's effectiveness and job satisfaction. CHPs' job satisfaction was highly associated with marital status, education attainment, and motivation to apply as a CHP [4]. CHP who was married, had a bachelor's degree, and had a higher reason to work were more likely to have higher job satisfaction than their counterparts [4]. In general related to rural health workers, the two-factor theory divided retention factors into extrinsic and intrinsic factors [6]. The workplace provides extrinsic factors (e.g., salary, work status, security) while intrinsic factors are inherent in work (e.g., autonomy, the significance of work) [7]. Lehmann et al. [8] emphasized a multi-dimensional approach extending the retention factors from the individual, local environment, work environment, and national environment to the international environment (i.e., health worker shortage in high-income countries).

Furthermore, review studies observed rural nurse retention factors based on the WHO standard (i.e., education and professional development, regulatory interventions, financial incentives, personal and professional support) [9, 10, 11]. In addition, family and community factors were also emphasized with the association with job satisfaction [12, 13]. However, previous frameworks did not explain chronological changes while rural nurses worked long-term. In other words, rural nurses experienced 'transitions' adjusting to the environment, social surroundings, and professional roles [14, 15]. Therefore, this study aims to explore the retention factors of the CHPs working for over 20 years in South Korea based on the combination of a multi-dimensional framework and transition-related factors in previous literatures [8, 14, 15].

|

METHODS

|

This is a qualitative study based on a narrative approach to obtain descriptions of the CHPs' experiences over 20 years [16]. Three research questions were asked: 1) what the significant finding of the CHPs' retention factors was; 2) how do the contexts based on the multi-dimensional perspectives differ from personal or external transitions; and 3) what implications could CHPs provide about retention factors to other countries experiencing primary health care provider (i.e., community nurses) shortage in rural or remote areas. Ground theory analysis was used to illustrate the retention factors not explained in previous theories to analyze multi-dimensions and transition processes.

1. Participants

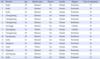

We recruited the participants by purposive sampling based on representative information [17]. The inclusion criteria were CHPs who worked for more than 20 years, including retired CHPs. Retired CHPs were included to observe their reflections without interacting with the community. One participant's work experience was less than 20 years but was included because the case represented working on the island (Case 13 in Table 1). The characteristics of the 16 participants are presented in (Table 1). The most extended work experience was 34 years, and the least was 25 years (excluding Case 13). Twelve CHPs were retired, and four CHPs were still working. All the participants were female and had religious faith.

|

2. Data Collection

The authors conducted 16 interviews from August 2014 to November 2014. Initial interviews were in-person, and further interviews were done in person or by telephone. The interview lasted 90~120 minutes, and questions were designed based on the life flow of the participants starting from the first experience as a CHP, working as a CHP, and reflection. Interviews were recorded, transcribed, and saved. The initial research design and questions were based on one of the CHP's photo essays [18]. Moreover, the research design was modified based on specialized qualitative researchers' feedback. After the interview, the research team cross-checked for validity.

3. Data Analysis

This study used grounded theory to analyze the process of open coding, axial coding, and selective coding [19, 20]. First, the data were analyzed using open coding, a line-by-line examination of the transcribed text to create codes. Next, the data were analyzed as axial coding, which sorted the data with relevant codes and categories [21]. The result section is mainly based on the axial coding analysis to focus primarily on the research questions. To ensure reliability and validity: 1) truth value or credibility; 2) transferability; 3) consistency and dependability were considered in the study design [22]. First, truth-value or credibility was met by the experience of the researcher working in Africa as a nurse volunteer, which allowed a better understanding of working in a setting lacking infrastructure. Second, the transferability was met by cross-checking between the researchers during the interview and analysis. Also, three participants volunteered to cross-check the codes related to the themes and categories from their transcriptions. Third, consistency and dependability were met by three other qualitative researchers evaluating the process and outcomes of the study analysis.

4. Ethical Consideration

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of the institution where the first author was affiliated before data collection (IRB No.1409/002-006). Written informed consent was obtained from each participant before the interview.

|

RESULTS

|

The CHPs' retention factors are presented in (Figure 1). The central phenomenon of the study was working as a CHP in rural areas for more than 20 years in South Korea. This paper mainly focused on the causal conditions, contextual conditions, intervening conditions, and consequences, and the narratives from the CHPs are followed.

|

1. Causal Conditions

The definition of causal conditions relates to events or incidents that lead to occurrence or development [19]. The initiation of being a CHP was connected to being a nurse considering 'financial issues, family background, career path, experience from early childhood, and values related to faith/religion'. Most participants were the 'first daughter' or 'the representative household'. Therefore, 'financial reasons' facilitated the motivation to apply as a nurse or a CHP. Most CHPs still carried the financial accountability after marriage due to the husband not having a regular job (e.g., pastor, freelance artist).

I had six siblings: two brothers and four sisters who were all younger than me. When my mother was not at home, my father told me to do all the chores instead of my mom because I was the 'first daughter.' (Participant 8)

My teacher recommended applying for the CHP scholarship so I can exempt my tuition fee for college. Also, I didn't have to worry about what to do after graduation. (Participant 1)

Those who applied voluntarily were motivated by the'autonomy' of the job, had 'personal experiences' being sick as a child, or enjoyed taking care of people when they were young. Furthermore, sometimes the motivation was related to the participant's 'religious belief' and thought being a CHP was one of their callings. Interestingly, all 16 participants said they have a religion. Eleven out of 16 participants were Christians, and three were married to a pastor.

I even brought the first aid kit when we went on a school field trip. (Participant 14)

The most beautiful thing was that CHP could work independently as a nurse. The second one was able to provide direct healthcare service to the community. The third thing is related to religion. I wanted to spread the Gospel as a Christian. (Participant 2)

Based on the narratives, applying for a CHP was closely related to the historical context of the 1970~80ths in South Korea. When the participants were in their early childhood, they strongly preferred 'having a son'. Therefore, it was challenging to be well-educated as a 'daughter'. On the contrary, some parents, especially the mother, supported their daughters even in this social context and encouraged them to go to college and be nurses.

I eventually had a name after I graduated from elementary school. People used to call me Yunam (which means having a son). Praying for a son since we did not have one. (Participant 9)

I was the first girl to go to college since we were poor, and boys had the priority to be educated. (Participant 1)

2. Contextual Conditions

Contextual conditions are patterns of conditions that intersect dimensionally as time and place and are the circumstances' background [20]. The primary contextual condition in this study was getting adjusted to the environment, work, and community.

1) Environment adjustment

The environmental adaptation was about the participants' adaptation to the characteristics of the rural and remote areas, mostly in farming and fishing areas. The assigned regions were mainly challenging to the CHPs, especially in their initiation state. In particular, the participants who grew up in urban areas had a more difficult time than others. 'Tears' was the representative concept that reflected the difficulty of adjusting to the first assigned environment. The harsh climate made participants feel 'isolated' and 'missed the outside lives'. For example, the 'neon sign' was a symbolic expression of city life. Besides,'feeling threatened' was one of the enormous challenges the participants went through.

There were a lot of briquette accidents. One of our seniors was sleeping with her mother, and they were dead. Because of the briquette. Even the mother and the senior. There were also suicidal accidents. One CHP used the mental health-related medicine 'phenobarbital' to suicide… Since there was no safeguard at that time… some people went through sexual violence from the male community members got married and stayed there for good. (Participant 1)

That place didn't have any toilets, so I had to go to the field. I had to pipe water from the ground to make supper. That made me cry all day. It was more than I imagined. I knew nothing and went there. I expected basic supplies would have been there because it was called a 'health clinic'. (Participant 12)

Most of the participants had a difficult time adjusting to the remote areas. When assigned to island regions, most CHPs avoided them; they expressed they went through a more challenging situation than others. The lack of transportation and resource was the hardest part. However, since the environmental condition was challenging, the community members were desperate to make the CHPs stay in their community.

Since nobody wanted to come, we had to stay at least three years, and if nobody came, it meant we had to stay there for our graves. (Participant 13)

Considering the occupational environment as a positive perspective was related to having the authority to choose the area. When the assigned area was a familiar place like their hometown facilitated the designated area's adaptation. A few respondents perceived the rural area as 'beautiful nature'. They were amazed by the visuals and sounds of nature. In the initial phase, the primary economic industry in rural areas was farming or fishing. The community started early morning, around 4:30 am, which could assume when the patients would visit.

If I go to the village, it looks like seeing a classical picture. The kids had snots on their noses, and people were making dinner by collecting logs. It felt like a different place. It was good. We travel to these places on purpose! I felt like traveling. Ha-ha… When I went to the G area, I intentionally went by the dirt road, which was unpaved for my pleasure. (Participant 3)

2) Work adjustment

CHPs handled preventive care, health education, and health projects. Therefore, the participants had a more comprehensive range of work roles than clinical nurses.'Lack of professional training' and 'discrimination' made it challenging to get used to the CHP work. Respondents emphasized 'education' in this context for professional and self-development. There were workshops and training programs related to advanced clinical knowledge. Some enjoyed learning how to diagnose and prescribe medicine; however, others 'felt discriminated' and ignored by the instructors, who were primarily medical doctors.'Lack of administration support' indicates the lack of support from the official government. Participants felt lonely by not having enough administration support and working separately. Even essential resources (e.g., medicine, paper) were not enough; some CHPs had to borrow and collect recycled papers for prescription sheets.

I had to home visit without any medicine. People don't know us. So they start with "Who are you?". We had to start introducing ourselves. Even the health center staff did not know who we were and was unfamiliar with the CHP program. (Participant 5)

The burden of work was related to 'clinical experiences'. Participants with clinical experience felt less load than their counterparts. The participants felt the most fear when'performing suture', 'performing dressing in wounds', or'making a diagnosis', which was typically a doctor's job. At the same time, clinical performances built up 'confidence' as 'professionals'. The most challenging works were'delivering a baby' and 'acting for emergency issues'. Since these issues were all related to 'life-threatening' problems, the participants expressed the hardship of handling the pressure. There were cases where the CHPs delivered a baby on the bus or unexpected twins. 'The sound of the tractor or motorcycle' was the sound of the 'precursor of emergency cases'.

The sound of the tractor.. even when I was sleeping, if I heard a sound of the tractor, I automatically woke up and said, 'Ah! A Patient!' but then I realized I was at home. Also, when I am at the clinic and hear the sound of the tractor. I get tensed. The motorcycle sound.. I carefully listen to if it will pass by or stop at the clinic. When it's the clinic, the clinic turns into an emergency room. If it gives by… hwww.. it's not an emergency. (Participant 5)

Also, the 'managing community health programs' role led to extra work loading. Unlike clinical nurses, CHPs had to manage 'health-promoting education' like promoting physical activity', opening 'gymnastic programs', or'dance schools'. On the other hand, some CHPs considered this role 'positive' and 'felt autonomous' in their career than their clinical duties and put more 'passion' into these community health programs.

For extra, we had to provide health education or health promotion related programs like 'walking movement' or 'aerobic classes'. I invited gymnastic instructors and taught the community members sports dance, yoga, and stretching for 80 participants. Whenever the clinic was over, the community members gathered in front of the clinic and danced together. I stood up the stairs and guided the group, and the group was dancing and dancing even though they were sweating. It was so much fun. (Participant 11)

3) Community adjustment

Along with adapting to the environment and work,'being a true community member' was another retention factor. Different locations had different community cultures based on regional history. The CHPs needed time to learn about the community members' personal and provincial history. Since the CHPs personally had different unique backgrounds and were higher educated women, there was a distance between the community members, especially among women community members.

Most of the community members called me Chief… But the woman next to me started to call me my name, saying I was the same age as her. I was embarrassed and didn't know what to say. (Participant 4)

Remote areas were unique and related to higher needs for primary health care than other sites. Moreover, remote areas had more complicated histories associated with the national history of South Korea. CHPs who worked in more isolated areas, like in the island areas, described being treated like a 'queen' or a 'celebrity'.

The more remote area you are assigned, the more queen you can be. I was on a faraway island, and the director always called me My highness. (Participant 16)

3. Intervening Conditions

1) Encountering lifetime crisis

While the CHPs were adjusting and building coping strategies, various lifetime crises came along. There were'stressful events', 'relationship conflicts', and 'work pressure' that led to 'feeling exhausted' and 'powerless'. As a standard narrative, the participants mentioned the first five years of working were the most stressful period at the same time when their children were still young.

In the stage of attachment, my baby didn't want to let go of me. It was a war every morning to go to work. The baby cried like hell. It didn't let me go blocking me from going to work. (Participant 10)

'Stressful events' included health problems and lack of welfare. Three participants suffered severe health problems due to workload, not getting enough sleep, and eating poorly. Even in cancer, the CHPs still had to work with their painful health condition. They also felt embarrassed about not managing their health well while being a health provider.

When I was diagnosed with cancer, we were part-time workers. We didn't have any official leave for illness. So how did I go through it? I had the surgery, got discharged, and stayed with my sister for a day. I returned the next day, rested for two days, and went back to work. (Participant 11)

'Relationship conflict' included the relationship between family, community members, and health officers. The relationship conflict was deeply connected with the multiple roles of the CHPs. They had to be mothers and wives at home while they were the community's leading primary health providers. The CHPs who had children (15 out of 16) especially mentioned the hardship when their children were in the 'attachment stage' aged 0~2 years old and in the 'youth' stage. When the CHP's children were in the stage of youth, they claimed their mother cared more about the community than themselves. Due to the lack of educational resources, the CHPs went through conflicts between their family about 'education' and 'college issues'.

I breastfed all of my three children while I was working in the community health post. Someone to help? Nonsense! It was real. All three. (Participant 2)

My daughter said, 'You only care about the grandmas than me!'. (Participant 4)

Moreover, the CHPs had to deal with the dynamics among the community members. The CHPs mentioned it was hard to consider the community's various needs, mainly when the opinions were divided in the opposite direction.

[To the community members], I turned into a 'yes man'. In any case, I had to say yes. Yes. Yes. That also made me say 'yes' always to my husband and my kids. I think I forgot to express my own opinion. (Participant 6)

'Work pressure' mainly came from the regional health government office while the health system and social status of primary health were changing dynamically in the 1990s. The position of the CHP changed from a special officer position to a regular full-time job. The change of social status made the CHPs stable but with more restrictions and guidelines to follow. Some of the CHPs also were reshuffled to another region without any notice. The elder CHPs felt they lost their authority in managing health programs and administration work. It also led some CHPs to request an earlier retirement.

They said we had done a great job. Great job. But the medical associations, the doctors, wanted us to disappear. We had to hear we would disappear every time we went through the workshop. I hated that. (Participant 12)

2) Coping Strategy 1. Self-effort

To overcome the crisis related to the environment, work, and the community, the CHPs tried to 'improve the poor working condition', 'develop their professional needs', and 'try to be united with the community'. First, some CHPs tried to remodel the community health post themselves. They visited other community health posts to benchmark and made a budget for remodeling.

I saved money to remodel this place [the health post] for ten years. I used cypress for the ceiling and put in so much effort. Even the electricity cords.. because some seniors forget to turn it off… With the money, we saved…. (Participant 2)

Most of the CHPs had more confidence when they made their work strategy. Some CHPs put passion into home visiting care and try to think from a patient-centered perspective. Some CHPs registered extra training courses for professional development like 'hospice training', 'nursing graduate school', and 'nurse practitioner programs'.

I stayed in the health post in the morning. In the afternoon, I went to the field because I had a car and gave the Intramuscular (IM) medicines that were working. I also delivered the medicine to their home with the name tags. (Participant 13)

There was a turning point when the CHPs felt they started to be 'united with the community'. This strongly motivated the CHPs to maintain to stay in the area. At first, the CHPs expressed having an overlapping identity'being a representative of the community members' and'being a member of the government at the same time'. They had role conflict when issues related to the federal policy and the community protested against that. The CHPs who stood on the community members' side got more trust and respect.

The official worker told me to apologize to the mayor. They also told me to agree on every subject with the mayor. They expected me to grab the microphone and insist that I agreed with the mayor. But how could I stay against the community where 99% disagreed with the mayor's opinion. I thought that was betraying. (Participant 8)

Another piece of evidence is that the CHPs were accepted as community members when invited to the community's events like school events, village competition events, and traveling.

I turned out to be the one who has to be with them on every occasion. They invited me to the school's sports events and picnics. The elders invited me when they were going on a travel. I happily went to every event and traveled. I could feel them perceiving me as a community member, not a government officer. (Participant 7)

3) Coping Strategy 2. Social support system

'Supportive system' was the positive enforcement for CHPs dealing with community health issues. It included relationships with the upper-level health officials in the public health center, colleagues in the same cohort, community members, and family. Having positive relationships with the health officials was essential for processing administration-related tasks. One CHP with experience working in the health center represented an ideal mediator between the health officials and the community members. However, most CHPs felt uncomfortable communicating with the health officials.

Representative community members organized the community steering committees (CSC). A good relationship with the community committee, especially the village health workers (VHW), was a significant factor in effectively adjusting to the community and promoting primary health care. This teamwork helped the CHP get closer to the community and effectively apply health education and health promotion activities.

Some participants shared their hard times with their cohort members. CHPs said since the colleagues were distant, it was helpful to each other that they could keep each other secrets. One participant was having annual meetings with their cohort for ten years. Another participant had monthly meetings with the members in the same region. Having a solid membership motivated the CHPs to remain their work.

The majority of the participants were married and had children. Therefore, the life of being a CHP had to interact with life as being a woman. The participants had to manage the community's health while dealing with their own life as wives and mothers. However, it was hard to expect maternal welfare from the federal government. That made the family support more critical for the participants to continue working.

I think it was 1999.. Do you remember it snowed 10 feet? I remember holding my medical kit and my husband pushing down the snow in front of our house. If he pushed the snow down before me, I stepped forward. I think we did that over 30 minutes to reach a patient. (Participant 14)

4. Consequences

'External change' implies the natural 'maturation' across time-related to historical, economic, and systematic change related to the primary healthcare system of Korea. 'Changes in the health system', 'changes of social status', and 'aging' were the keywords in this category. ‘Changes in the health system' included the national health insurance system. The participants mentioned that the health post was considered a 'real health center' after the health insurance system settled down. 'Establishment of the infrastructure' was closely related to environmental improvement. It increased the effectiveness, safety, and accessibility of transportation. The health status seemed to improve due to advanced medical services.

At first, there were a lot of digestive problems. Most people didn't have a refrigerator in their homes. Most people didn't know they had to take parasiticide regularly. Also, there were many skin problems because they couldn't wash very often. (Participant 12)

'Change of social status' was related to the change of employment status to 'officials in special government service', which was a temporary position to a 'regular officer' job. The transition led to stable employment status and wages. Most participants recalled the status change to a'general' position had advantages on the administration system but had more restrictions related to health projects. Since the participants enjoyed the autonomy to plan and design health projects, having limited options was a high-stress factor, even considering retiring earlier.

The keyword 'aging' meant various meanings: aging of CHP themselves, their children, family, and community members. While industrialization was rapidly spreading in South Korea, most young people moved to the city for jobs and education. The residents who remained in the community transitioned into the aging population. The CHPs felt they were aging together with the community members. Moreover, since their children were also growing up, the CHPs mentioned their obstacles to raising children disappeared 'naturally'.

I realized I could understand the community members better when I turned in my 40s. You know we only try to follow the textbooks in our 30s. But now, when I hear about the family conflict between the mother and daughter-in-law, I can understand better. (Participant 14)

In the end, most CHPs mentioned 'settlement'. The CHPs and their family felt the community was their 'home' now. For a long time, living together led the CHPs to know each other naturally, which also motivated the CHPs to stay longer.

We even know the numbers of spoons of each household. How many children they have, their main stressors, and what kind of symptoms they have to be aware of. We know almost everything. (Participant 9)

|

DISCUSSION

|

This study was based on the narratives of the CHPs who worked for over 20 years in South Korea. This study used grounded theory for analyses [20]. The central phenomenon of the study was the retention factors for long service. The causal condition was related to applying for the CHP position, such as 'motivation'. The contextual condition was based on 'adjustment to the environment-work-community'. Well-adjustment and balance of life were significant factors for remaining to work. Next, building 'coping strategies' and 'social support systems' were the intervening conditions while the CHPs went through various 'life-time crises'(e.g., personal health problems, work pressure). Ultimately, 'maturation through transitions' and 'external changes' were brought up as consequences.

The findings of the retention factors among Korean CHPs aligned with previous literature but extended the factors related to chronological transitions. As the two-factor theory derived [6], Korean CHPs still considered intrinsic factors (e.g., autonomy, the meaning of work) and external factors (e.g., salary, security) significant, especially in the initial stage of work. The multi-dimensional approach, including retention factors from the individual, environment, and national regulations, was emphasized during the mid-stage of the CHPs around 5~15 years of work [8, 9, 10, 11]. Specifically, Environment-Work-Community adjustment was the key factor remaining to work as a CHP in the rural community. However, the multi-dimensional approach could not explain the dynamic related to the historical changes (e.g., economic development of Korea) or life transitions (e.g., aging). Therefore, this study combined the theory of transitions [15] to explain the transition factors (e.g., growth by life span) which occurred during the long-term experience and how CHPs overcame the changes by building up coping strategies and support systems.

Considering the findings, what implications could the CHPs provide to rural nurses from a global perspective? First, external factors related to robust primary health systems should coexist with individual or organizational retention factors [10, 23]. Without external factors, individuals working as CHPs could be victimized in unsafe environments, predominantly female nurses. Several times during the interview, these cases were mentioned, and observed that CHPs had to quit or be reinforced to marriage due to sexual violence. Due to the harsh environment (e.g., lack of security), the community members could break into the health post during the night where the CHP was living alone. Moreover, there were CHPs accidents related to gas exposure due to carbon monoxide poisoning from the inadequate heating system. Secondly, 'social support systems' for rural and remote nurses were critical in each major'transition' stage. We mainly focused on social networks in the analysis; however, this concept is an integrative concept for the implication. The social support system is the most critical factor that should be applied better to adjust to personal-work-community, build up effective coping strategies, and improve access to external factors [1, 13, 24]. For example, implementing a mentoring program like matching an experienced nurse and a newcomer may influence the individual perspective and increase the information and access through organizational and systematic (i.e., national) level [13, 24]. Third, despite external changes, personal factors like 'callings' and 'commitment' were still significant similar to the previous study [25]. This indicates intrinsic motivation was crucial as financial incentives, which is still a debatable issue related to maintaining health professionals in rural or remote areas [8, 26].

This study has several limitations. The narratives of the respondents could have social desirability bias. Although the CHPs relied on their memory, they could share information the researchers expected to hear. We tried to probe this issue by interviewing the respondents three times to check the narratives' reliability. Secondly, since this case relies on South Korea's context to work in the 1980s, generalizability can be violated. This also applies within the country because different regions have different community cultures. In the study design, we did not consider the ex-CHPs who could have provided attrition factors [2]. This research also did not include the next generation of CHPs who could provide recent insights into retention factors. Since different ‘external changes' are required in current healthcare services (i.e., virtual clinical practice in the pandemic situation), the new generation of CHPs may experience different patterns related to retention factors for long service.

|

CONCLUSION

|

This study found retention factors in multilevel dimensions, from individual to national factors. Considering the external factors (i.e., primary health care system) and chronological nature of ‘transitions' could implicate another insight when conducting rural nurses globally. Furthermore, the CHPs built their adjustment strategy in the environment, work, and the community, while rapid external changes were occurring. Interestingly, some retention factors occurred naturally with chronological changes based on 'transitions', primarily related to maturation in person, family, and the community. For further study, we suggest a multi-dimensional approach to the next generation of CHPs, including the pandemic generation in 2019, could provide modern political insights to prevent insecurity and isolation among rural and remote area nurses.

|

Notes

|

This article is a revision of the first author's master thesis from Seoul National University.

|

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

|

The authors would like to thank all the Community Health Practitioners who, despite their busy schedules, gave time to participate in this study. We would also like to thank the Community Health Practitioner Association, which helped recruit participants for this study. HP would like to thank Dr. CY Kim, Dr. SH Yoo, and Dr. BH Cho for their guidance during the master's thesis process.

|

References

|

KACHN

KACHN

Cite

Cite